| Home | Blog | Ask This | Showcase | Commentary | Comments | About Us | Contributors | Contact Us |

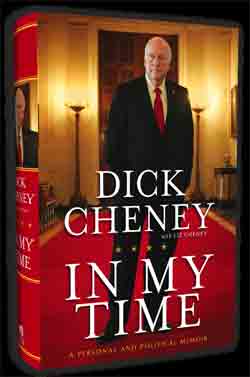

11 questions reporters should be asking Dick CheneyASK THIS | August 243, 2011As the former vice president uses media interviews to sell books, reporters have an unprecedented opportunity to confront him about his highly controversial legacy and push him to divulge more about how he pursued his agenda. (Also published at The Huffington Post, where you can vote for your favorite questions.) By Dan Froomkin Dick Cheney has spent his career not revealing himself, and in his new memoir and the ensuing PR blitz, he appears to be staying largely in character. But as the former vice president uses media interviews to sell books, reporters have an unprecedented opportunity to confront him about his highly controversial legacy and push him to divulge more about how he pursued his agenda. And there's so much material -- starting of course with Cheney's cheerful acknowledgment of his role in promoting governmental conduct that is flatly illegal and conflicts with traditional American values. Here are some questions journalists could be asking Cheney -- and, most importantly, some facts he should not be allowed to escape. Q. How can you possibly not call it torture? And just how involved in it were you? Waterboarding -- no matter what Cheney says -- has been one of the most notorious forms of torture dating all the way back to the Spanish Inquisition. It involves strapping people to a board and, by pouring water over their face, essentially drowning them, before reviving them and possibly doing it again. The U.S. government has historically considered it a war crime. In 2003, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the 9/11 mastermind, was waterboarded 183 times in one month. When asked if he still embraces waterboarding during the first interview in the lead up to the release of his new memoir, "In My Time," Cheney said: "I would strongly support using it again if circumstances arose where we had a high-value detainee and that was the only way we could get him to talk." Given that waterboarding is so obviously illegal, Human Rights First official Dixon Osburn suggests this line of questioning: "Do you fear being charged with criminal conduct? Do you fear being charged with a war crime? The United States has prosecuted individuals who engaged in waterboarding, so why is there now an exemption from those in the Bush administration?" Former prosecutor Elizabeth Holtzman, who served on the House Judiciary Committee during Watergate and later advocated for Bush's impeachment, said she would like reporters to explore how involved Cheney was in approving individual interrogations. "What role did he play in feeding questions to the people being tortured?" she asked. "Did he suggest questions?" Holtzman also suggested that that Cheney be asked how worried he was that he'd be prosecuted for war crimes once the Supreme Court overruled the administration and declared that detainees were subject to protections under the Geneva Conventions. And since the possibility of international prosecution for war crimes still exists, she said, "when does he plan to travel outside the Unisted States next?" "I would ask him about the case of Khalid al Masri," said Scott Horton, a human rights lawyer and columnist for Harper's magazine. "Did you participate in the decision to have him apprehended and sent to be held in Afghanistan? Were you aware of the techniques that would be used on him?" Masri, who was swept into custody because his name was similar to that of an associate of a 9/11 hijacker, turned out to be an unemployed father of five who had done nothing wrong. Horton said there were considerable doubts within the White House's own National Security Council regarding Masri's identity. "But in the end, the authority was given to seize this guy and torture him." Horton also cited the case of Haji Pacha Wazir, initially described by officials as al Qaeda's banker. He was seized by the CIA in 2002 and held in prisons in Morocco and Afghanistan. Although by 2004, two CIA case agents had determined the accusations against Wazir were baseless, Wazir wasn't released until 2010. "Was that a correct thing to do? Were you involved in that decision?" Horton asks. "Was it appropriate to continue to hold him after it became clear that he wasn't guilty of anything?" Q. Why torture detainees if, on top of everything else, it doesn't even work? Given that torture is illegal, immoral and contrary to core American values, some critics blanch at debating its effectiveness. But Cheney's assertion that the administration's interrogation techniques somehow paid off needs to be exposed as a myth. In his memoir, for instance, Cheney asserts that: "In May 2011, after the U.S. located and killed Osama bin Laden, we learned that intelligence gained by these interrogators through the enhanced interrogation program had helped lead us to him." But experienced interrogators and intelligence professionals reached the exact opposite conclusion, determining bin Laden could have been caught much earlier had those detainees been interrogated properly. "It's remarkable that in that debate, the fact that torture was demonstrably ineffective is used as proof that it worked," said American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney Alex Abdo. In fact, every example that Cheney or Bush have cited of American lives saved through brutal interrogation techniques -- including the familiar ones Cheney repeats in his memoir -- has been debunked by investigative reporters. Dixon Osburn, director of law and security at Human Rights First, a nonpartisan nonprofit supporting international human rights, suggests the following question: "The near-unanimous opinion of retired generals and admirals and the near-unanimous opinion of professional interrogators is that torture is counter-productive and unreliable. Why in this circumstance do you not agree?" Cheney should also be asked at what point he was made aware that the techniques he was advocating had historically been used to elicit false confessions, and why he pursued them anyway. Cheney writes in his memoir that interrogation techniques "were based on the Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape Program used to prepare our military men and women in case they should be captured, detained or interrogated." Here are some follow-up questions: Does he realize that the SERE program was reverse-engineered from methods used by Chinese Communists to extract confessions from captured U.S. servicemen that they could then use for propaganda during the Korean War? When he found that out, what was his reaction? What is his response to critics who say he has engaged in a perverse emulation of our enemies' worst behavior? And when did he first learn that the sole source for a key pre-war assertions made by the administration -- that Iraq had trained al Qaeda to make bombs, poisons and deadly gases -- was a confession extracted under torture by Egyptian authorities from Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, a captured terror suspect who had been rendered to Egypt by the CIA? Did he continue to cite that information anyway? Who told him, and how did he respond? Q. What do you consider a violation of human dignity, exactly? Cheney has consistently been able to limit his discussion about Bush-era abuses to what the CIA did to "high-value" terror suspects. But in the years following 9/11, brutal conduct extended much farther and wider than that -- the premier example, of course, being the horrific abuse that took place at the Abu Ghraib prison. Denying that Bush White House policy was responsible for what happened at Abu Ghraib has been the central goal of a disinformation campaign that began almost as soon as the photos went public in 2004 and continues to this day. In a May 2009 speech, for instance, Cheney insisted that "it takes a deeply unfair cast of mind to equate the disgraces of Abu Ghraib with the lawful, skillful and entirely honorable work of CIA personnel trained to deal with a few malevolent men." But just 18 months earlier, a bipartisan report from the Senate Armed Services Committee had made that connection explicitly. "The abuse of detainees in U.S. custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of 'a few bad apples' acting on their own," the report found. "The fact is that senior officials in the United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their legality, and authorized their use against detainees." The report noted that in December 2002, just four months after Justice Department lawyers working closely with Cheney's office drafted what became known as the Torture Memos, then-defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld signed and approved a memo authorizing military interrogators at Guantanamo to apply such techniques as stress positions, hooding, sustained isolation, sleep deprivation, nudity, prolonged exposure to cold and the use of dogs. "[I]nterrogation policies and plans approved by senior military and civilian officials conveyed the message that physical pressures and degradation were appropriate treatment for detainees in U.S. military custody," the report concluded. "What followed was an erosion in standards dictating that detainees be treated humanely." So perhaps Cheney should be read a list of techniques widely used on garden-variety detainees, many of whom turned out to be innocent. Which of the following does he consider a violation of human dignity, and which does he consider an appropriate interrogation technique? Items for the list would include: forced nudity, isolation, bombardment with noise and light, deprivation of food, forced standing, repeated beatings, applications of cold water, the use of dogs, slamming prisoners into walls, shackling them in stress positions and keeping them awake for as long as 180 hours. How would he feel if American servicemen -- or ordinary civilians -- were treated like that by another government? Q. At what precise moment did you conclude that war with Iraq was inevitable? This is a trick question. No matter what Cheney might say about the matter, there is now an abundance of documentary evidence -- in the form of leaks, unclassified memos, witness interviews and other people's memoirs -- definitively proving that Cheney and Bush had been gunning for Saddam Hussein since the moment they arrived in office. The war, in short, was inevitable all along -- pending the development of a sufficiently persuasive excuse. The first concrete evidence emerged in Ron Suskind's 2004 book "The Price of Loyalty," in which former treasury secretary Paul O'Neill described how Bush and Cheney put Iraq at the top of their agenda at their very first National Security Council meeting. "From the start, we were building the case against Hussein and looking at how we could take him out and change Iraq into a new country," O'Neill said. "And, if we did that, it would solve everything. It was about finding a way to do it. That was the tone of it -- the president saying, 'Fine. Go find me a way to do this.' " In 2005, the public got its first look at the Downing Street Memo, conveying a British intelligence official's conclusion in 2002 that President Bush was manipulating intelligence to build support for war with Iraq -- and that he was already set on invasion long before acknowledging as much in public. Paul R. Pillar, the intelligence community's former senior analyst for the Middle East, wrote in 2006 that the administration made its case for war by intentionally misinterpreting and cherry-picking official intelligence that, to the contrary, had concluded that deterrence of Iraq was working, and that the best way to deal with the weapons problem was through an aggressive inspections program. In 2008, an exhaustive Senate Intelligence Committee report determined that Cheney, Bush and other top officials had repeatedly overstated the Iraqi threat and incorrectly conflated it with the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. More and more evidence has emerged, including a major National Security Archives analysis last October of the historical record, including a new trove of formerly secret records. John Prados, co-director of the archives' Iraq Documentation Project, described "an early and focused push to prepare war plans and enlist allies regardless of conflicting intelligence about Iraq's threat and the evident difficulties in garnering global support." And the analysis also called attention to what was missing, namely "any indication whatsoever from the declassified record to date that top Bush administration officials seriously considered an alternative to war." So Suskind, in an interview, proposed this line of questioning for Cheney: "I would ask him why, if intelligence reports showed that Saddam was defanged ... why in the first National Security Council meeting was it decided that he is the number one priority of United States policy and that he must be removed? How does that fit with the United States' national interest? Why not admit that that was the centerpiece of U.S. policy from the very beginning? Instead of having to go back through the mendacious acrobatics of attempting to justify the Iraq War." Q. Did you tell Scooter Libby to leak Valerie Plame's identity as a CIA agent to the press? Scooter Libby, who had been Cheney's top aide, was found guilty of perjury and obstruction of justice in March 2007 -- and there was essentially no doubt in anyone's mind whom he was lying for. Back in the summer of 2003, after former ambassador Joseph Wilson suggested that the administration manipulated intelligence about Saddam Hussein's weapons programs to justify that spring's invasion of Iraq, Libby -- along with two other administration officials -- outed Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, as a CIA agent to reporters. But when FBI agents asked Libby why he did it, he lied -- presumably to keep Cheney's role secret -- and said he was simply passing along information he'd heard from another journalist. In his final arguments before the jury, special counsel Patrick J. Fitzgerald argued that Cheney and Libby were intensely focused on discrediting Wilson, and decided to tell reporters -- including then-New York Times reporter Judith Miller -- about Wilson's wife working for the CIA as a way to cast suspicion on his mission and his claim. "There is a cloud over what the vice president did that week," Fitzgerald said. "He sent Libby off to Judith Miller at the St. Regis Hotel. At that meeting, ... the defendant talked about the wife. We didn't put that cloud there. That cloud remains because the defendant has obstructed justice and lied about what happened." "He's put the doubt into whatever happened that week, whatever is going on between the vice president and the defendant," Fitzgerald continued. It was established at trial and in court papers that it was Cheney who first told Libby about Plame's identity as a CIA agent, that Libby actually acknowledged to the FBI that he might have discussed Plame's employment at the specific direction of the vice president, and "that when the investigation began, Mr. Libby kept the Vice President apprised of his shifting accounts of how he claimed to have learned about Ms. Wilson's CIA employment." In the highly selective account of the affair in Cheney's memoir, the former vice president shrugs off the Libby case as a disagreement about recollections. But did Cheney in fact tell Libby to out Plame to reporters? Then did he ask Libby to lie about it to the FBI? Did he ever tell Libby to come clean? And why was it so important to keep the inner workings of his office so secret? Could it be because the Plame case was a microcosm of so much that was going on there? Q. Just how much surveillance do you think the government can conduct without a warrant? In his memoir, Cheney discloses that the government's huge warrantless surveillance program was his initiative. But much still remains unclear about the extent of Cheney's role -- and of the program itself. How involved was he in drafting the Justice Department memos that gave the program legal cover? Was his position that the program -- even as it was originally configured -- complied with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which limits the government's power to tap American phone lines? Or was his position that FISA was an unconstitutional restraint on the president, and therefore didn't need to be followed? Jack Goldsmith, the former head of the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, wrote in his book that Cheney counsel David Addington and others treated FISA the same way they handled other laws they objected to: "They blew through them in secret based on flimsy legal opinions that they guarded closely so no one could question the legal basis for the operations." Does Cheney share Addington's view that the country was just "one bomb away from getting rid of that obnoxious [FISA] court"? And would he encourage future presidents to ignore laws they don't think are constitutional? What exactly was the program doing that was so illegal that even Bush administration lawyers finally demanded it be amended? And what good did it all do in the end? "We've now learned that the National Security Agency has built the biggest haystack there is" said American Civil Liberties staff attorney Alex Abdo. But has it been of any use? How many solid leads has it generated? How many prosecutions? How many stopped plots? "We haven't heard word one about stopped plots," Abdo said. "We're told these things are necessary," he said. "But they seem more like a grab for power than real necessities." Q. What about all the spectacular blunders you don't mention in your book? As with many memoirs written by consequential people, the most interesting aspects of Cheney's book could be what he leaves out. Some key events he addresses in the book -- but with a remarkable absence of detail. But some he chooses not to mention at all. Scott Horton, a human rights lawyer who writes for Harper's, said reporters should be asking questions about the many issues that Cheney tries to ignore. One line of questioning Horton suggests, for instance, has to do with the November 2001 siege of Kunduz, a city in northern Afghanistan that at the time was the last Taliban stronghold in the country. Troops from the U.S.-allied Northern Alliance had the city surrounded, Horton said, "and American military intelligence believed at that time that most of the Al Qaeda and Taliban leadership were inside." But when Kunduz fell, "lo and behold, all these leadership figures they were expecting weren't there," Horton said. It turns out that during the siege, Pakistan asked the White House to allow the evacuation of Pakistani nationals -- "and against the advice of the intelligence community, Cheney authorized this, and the Pakistanis came in and took out all the people we were trying to get." Seymour Hersh recounted the airlift in the New Yorker, in 2002. And Ahmed Rashid wrote in his 2008 book "Descent into Chaos": "One senior (U.S.) intelligence analyst told me, 'The request was made by [then-Pakistani president Pervez] Musharraf to Bush, but Cheney took charge -- a token of who was handling Musharraf at the time. The approval was not shared with anyone at State, including Colin Powell, until well after the event. Musharraf said Pakistan needed to save its dignity and its valued people." Rashid wrote that one frustrated U.S. Special Operations Forces officer who watched the airlift from the surrounding high ground dubbed it "Operation Evil Airlift." Why did Cheney approve such a move -- and without any oversight? Does he have any regrets? Why did he feel he was the right person to make this decision? And what was his role in the aftermath? Did he suspect that an American-backed warlord would proceed to slaughter hundreds, perhaps thousands, of the prisoners taken in Kunduz? How was he able to block efforts to investigate that episode? "This is the essence of Dick Cheney and the sort of leader he's been." Horton said. Robert Kaiser, writing in the Washington Post, noted that Cheney leaves unaddressed another debacle that took place just a few weeks later: "The administration's failure to exploit the opportunity, at Tora Bora, to capture or kill Osama bin Laden in the early phase of the war in Afghanistan." And Cheney doesn't seem to have anything to say about why he and Bush didn't take the threat of a terrorist attack seriously before 9/11, when it could have made a difference. Former president Bill Clinton pointed that out in a Fox News interview in 2006 that he came "closer to killing" Osama bin Laden in a 1998 missile strike on terrorist training camps in Afghanistan than Bush ever did. "I didn't get him," Clinton said. "But at least I tried. ... They had eight months to try. They did not try. I tried. So I tried and failed. When I failed, I left a comprehensive anti-terror strategy and the best guy in the country, Dick Clarke, who got demoted." In his memoir, Cheney describes his meticulous attention to the "Presidential Daily Briefs" -- implying that he took them much more seriously than Bush did. Ron Suskind reported in his 2006 book "The One Percent Doctrine" that an unnamed CIA briefer flew to Bush's Texas ranch to call the president's attention personally to the now-famous Aug. 6, 2001, memo titled "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S." According to Suskind, Bush heard the briefer out, then told him as he left: "All right. You've covered your ass, now." What did Cheney do? Q. Who was really in charge the morning of 9/11? Cheney starts off his memoir with his recollections of Sept. 11, 2001. It's long been obvious that former president Bush underperformed that morning, but what remains unclear is whether Cheney, stepping into the void, exceeded his authority. The vice president is not part of the military chain of command -- and yet, when a military aide asked him whether the military should shoot down an apparently hijacked plane, Cheney authorized them to do so. "'Yes,' I said without hesitation," Cheney writes in his memoir. Asked a second time, he said yes again. Indeed, according to the final report from the 9/11 Commission: "His reaction was described by Scooter Libby as quick and decisive, 'in about the time it takes a batter to decide to swing.' " In his memoir, after describing his actions, Cheney provides the following explanation: "In one of our earlier calls, the president and I had discussed the fact that our combat air patrol -- the American fighter jets now airborne to defend the country -- would need rules of engagement. He had approved my recommendation that they be authorized to fire on a civilian airliner if it had been hijacked and would not divert." Bush, in his memoir, describes the conversation differently, giving himself a more leader-like role. "I told him that I would make decisions from the air and count on him to implement them on the ground," Bush wrote. "I told Dick that our pilots should contact suspicious planes and try to get them to land peacefully. If that failed, they had my authority to shoot them down. ... I had just made my first decision as a wartime commander in chief." Meanwhile, Josh Bolten, then the White House deputy chief of staff sitting near Cheney, wasn't sure any such conversation had actually taken place -- and, according to the 9/11 report, "suggested that the Vice President get in touch with the President and confirm the engage order." Bolten told the commission "he had not heard any prior discussion on the subject with the President." It turns out that the assertion that Bush gave Cheney the okay to shoot down planes is one of the few in the 9/11 commission's report that is supported solely by statements from Bush and Cheney themselves -- statements they made to the commission jointly and in secret, after refusing to face the panel alone or in public. "Among the sources that reflect other important events of that morning, there is no documentary evidence for this call," the commission found. "Others nearby who were taking notes, such as the Vice President's chief of staff, Scooter Libby, who sat next to him, and Mrs. Cheney, did not note a call between the President and Vice President immediately after the Vice President entered the conference room." Could Cheney and Bush have made up that conversation after the fact to prevent Bush from looking weak and Cheney from appearing to have been in charge? Keeping up appearances was certainly an issue from the get-go. Cheney, in his memoir, also describes his conclusion that afternoon that someone needed to speak to the public on behalf of the executive branch. "My past government experience, including my participation in Cold War-era continuity-of-government exercises, had prepared me to manage the crisis during those first few hours on 9/11," he writes, "but I knew that if I went out and spoke to the press, it would undermine the president." Q. Are you familiar with a man by the name of Karl Rove? George W. Bush had two great svengalis: Dick Cheney and Karl Rove. Indeed, one of the many great mysteries of the Bush White House remains whether Bush's two brains worked in tandem or at odds. Suggesting that Cheney's memoir doesn't answer that question is an understatement. According to its index, Rove is mentioned in all of six pages. The book is 576 pages long. Wasn't Rove a more significant figure than that? Aren't there any other stories Cheney has to tell? There were a few pretty strong indications here and there that the relationship had more than its share of animus. In the perjury trial of Cheney's top aide Scooter Libby, for instance, the opening argument by Libby's defense attorney was mostly about how Libby was being made a scapegoat by White House officials to protect Rove. Cheney apparently supported that view; Libby's team later introduced a note, handwritten by Cheney, that said: "Not going to protect one staffer + sacrifice the guy who was asked to stick his neck in the meat grinder because of the incompetence of others." As best anyone can tell, Rove and Cheney pretty much split the presidential portfolio, with Cheney taking lead on foreign policy, intelligence and energy and Rove taking the lead on most everything else. Cheney's memoir offers a glimpse of how he felt when Rove invaded his turf. Cheney describes the situation in the summer of 2007, when Bush was trying to figure out what to do about prolonging the surge of U.S. forces in Iraq, which was losing support in Congress. When Cheney found out that Bush himself was behind leaks to the press that he considered damaging, Cheney concluded, according to his memoir, that "The president was getting some bad advice from those on the staff urging a political compromise for our Iraq strategy." Cheney also describes finding out about a series of meetings being held to consider changing military strategy and thereby reduce political opposition. The meeting included national security adviser Stephen Hadley, chief of staff Josh Bolten, and Bush's three political counselors: Dan Bartlett, Ed Gillespie, and Rove. "Not only was this the absolute wrong time to send a message that we were wavering, it wasn't even good politics," Cheney writes. Q. Just how much had you had to drink before you shot your friend in the face? One Saturday afternoon in February 2006, while hunting quail in Texas, Cheney shot one of his fellow hunters, lawyer Harry Whittington, in the face. But he wasn't interviewed by law enforcement officials until the next morning. He and his staff didn't inform the media at all -- so the public only found out about it late the next day, after his hostess informed the local paper. He didn't make a public appearance for four days. And he'd been drinking. "Alcohol plus misuse of a firearm -- that's the sort of thing that ordinary people would find themselves in trouble with the law over," said Scott Horton, a human rights lawyer. "They might find themselves doing jail time," Horton said. Cheney expresses sadness over the shooting in his memoir -- but makes light of its epilogue. He writes that "the last thing on my mind was whether I was irritating the New York Times." The circumstances, however, remain suspicious. At the very least, Cheney has admitted to drinking a beer earlier in the day. But was it only one? Katharine Armstrong, a major Bush donor and lobbyist who hosted the hunt on her 50,000-acre ranch, told NBC News that she couldn't rule out the possibility that there were beers in the hunting party's coolers. "There may be a beer or two in there, but remember not everyone in the party was shooting," she said. The vice president's office ducked questions, referring reporters to the local sheriff's report. Cheney finally took questions on Wednesday -- from Fox News. "I had a beer at lunch," Cheney told Brit Hume. "After lunch we take a break, go back to ranch headquarters. Then we took about an hour-long tour of ranch, with a ranch hand driving the vehicle, looking at game. We didn't go back into the field to hunt quail until about, oh, sometime after 3 p.m. The five of us who were in that party were together all afternoon. Nobody was drinking, nobody was under the influence." But could Cheney have been negligent? Did nobody think of informing the media sooner? Why didn't he talk to law enforcement officials right away? Didn't his actions legitimately raise red flags? Q. How much did you know about Halliburton's massive bribery scheme in Nigeria? From 1995 to 2000, Cheney was the CEO of Halliburton, the engineering services company whose very name has become synonymous with crony capitalism and the corrupt intersection between government and the military-industrial complex. In 1998, he promoted Albert "Jack" Stanley to run Halliburton's large subsidiary, KBR. Stanley then proceeded to oversee a massive bribery scheme in which a consortium of companies including KBR paid out about $182 million in bribes to Nigerian government officials to secure $6 billion in contracts for the construction of liquefied natural gas facilities "There's just no way that amount of money was paid out without Cheney knowing about it," said Scott Horton of Harper's. "And then you look at how the settlement of this matter winds up." Indeed, Stanley's guilty plea was finalized in September 2008, just a few months before Bush and Cheney left office. How much did Cheney know about what Stanley was doing? Is it possible he could not have known? Or not had reason to suspect? And did he or his loyalists affect the investigation from the White House? Cheney's company also ended up reaping huge profits by bilking the government on billion-dollar sweetheart contracts, thanks to the war Cheney played such a major role in launching. How involved was he in steering those contracts to his former company? And can he really claim he had nothing to do with them, given that in one case disclosed by the Washington Post, a senior political appointee in the Defense Department chose Halliburton to secretly plan how to repair Iraqi oil fields -- months before the invasion, but only after running the idea past Cheney's chief of staff?

|

||||||||||||