| Home | Blog | Ask This | Showcase | Commentary | Comments | About Us | Contributors | Contact Us |

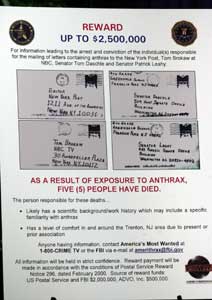

Whatever happened to the anthrax letters?ASK THIS | June 175, 2005Four years after the deadly anthrax attack on media and government offices, much remains a mystery. Bioterrorism expert Leonard Cole has some questions for the investigators on the case. By Leonard Cole Q. In November 2001, the FBI Web site indicated that the likely anthrax mailer was a disaffected loner who had access to a domestic laboratory. Did the FBI prematurely conclude that the perpetrator(s) had no overseas connection? Did the investigative focus on a domestic source diminish the pursuit of alternative possibilities? Q. In 2002, Steven Hatfill, an American research scientist, was named publicly by Attorney General John Ashcroft as “a person of interest” in the anthrax investigation. Although no charges were brought against him, Hatfill has been unable to find work and has sued the Q. A federal court judge recently ruled that the government must comply with Hatfill’s request for information about its investigation into the source of the anthrax. The government has not yet responded. Just what is the status of the FBI’s investigation? Why would making such information public compromise the investigation, as the government contends? Q. As a consequence of the anthrax letters, the nation’s 283 postal distribution and processing centers are being equipped with anthrax detection devices at a cost of about $600 million. Why install a device that can detect anthrax but not other potential agents such as botulinum toxin and ricin? Q. Bill Paliscak a former postal inspector, unknowingly received a face-full of anthrax-laden dust while working in 2001, and then developed symptoms of the disease (including difficulty breathing, swollen joints, fatigue). He remains very ill. Since none of his laboratory tests were positive for anthrax, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contends that his illness is unrelated to his exposure. The CDC’s position has caused consternation to Paliscak and his family. (See: After a Shower of Anthrax, an Illness and a Mystery, New York Times, June 7, 2005). Should the CDC not designate Paliscak a “suspect case,” a category included in the CDC’s protocol? What is the basis for diagnosis and case definition of anthrax and other diseases? Much about the deadly bioterror attacks in 2001 remains a mystery. Perhaps a half-dozen letters containing powdered anthrax bacteria were mailed in the In the course of the attacks, 22 people were diagnosed with anthrax. Eleven contracted the cutaneous form and all survived. But among the 11 who became ill from inhaling spores, five died. The first fatal victim died on October 5 in Florida, and the last on November 21 in Connecticut. Spores had leaked from the envelopes leaving a trail of contamination up and down the East Coast. Scores of buildings were evacuated and underwent decontamination including congressional offices, the Capitol, newsrooms, and postal facilities. More than 30,000 people at risk of exposure received prophylactic antibiotics, which doubtless saved lives. All this havoc was wreaked by a volume of anthrax powder equivalent to a handful of aspirin tablets. If the bacteria had been antibiotic-resistant and if hundreds of letters had been sent, the consequences could have been catastrophic.

|