| Home | Blog | Ask This | Showcase | Commentary | Comments | About Us | Contributors | Contact Us |

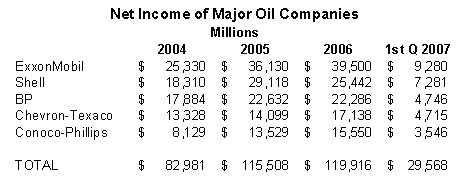

The method behind endless gasoline price spikesCOMMENTARY | June 166, 2007The oil companies have consciously reduced inventories while demand has been steadily growing. The result, as Peter Ashton puts it, is that whenever a refinery hiccups or a pipeline ruptures, there’s a dramatic spike in gas prices. By Peter K. Ashton PKAshton@aol.com Today, whenever a refinery hiccups, a pipeline ruptures, or consumers’ appetite for gasoline increases slightly more than expected, the response has been a dramatic increase in the price of gasoline. These increases are now routinely accompanied by the typical industry response that prices must go up in order to prevent shortages and to restrict price increases would interfere with market fundamentals and would cause long lines at the pump and widespread shortages. Of course, the response continues, these price increases are justified by the fundamental economic theory of supply and demand, and the resulting high profits generated by these price hikes are “healthy” for the industry. The economic implication of this latter statement is that these high profits will be reinvested in more refining and storage capacity so as to prevent such supply-demand disequilibria from recurring. Unfortunately, this is where fundamental economic theory has failed in practice. The data indicate that the industry has not been reinvesting in more capacity either in terms of production of gasoline or storage capacity, either of which could be used to offset the next supply disruption. The industry has been content to use economic theory as a justification for the gasoline price increases we regularly witness when supply is temporarily curtailed, but the industry ignores the crucial corollary economic principle of what should be done with the exorbitant profits once they flow into the industry’s coffers. Let us take a look at the magnitude of these profits that have been generated in recent years and where that money has gone. Oil Industry Profits No one, not even an industry spokesperson, will deny that profits have been extraordinarily high in recent years. A review of the net income of the five major integrated multinational majors indicates record profits in recent years as shown below in Table 1. Total profits for these five companies were $83 billion in 2004, rising by almost 40% in 2005 to $115 billion and rising another 4 percent in 2006 to almost $120 billion. First quarter 2007 indicates no change in this trend with profits of $30 billion.

Table 1

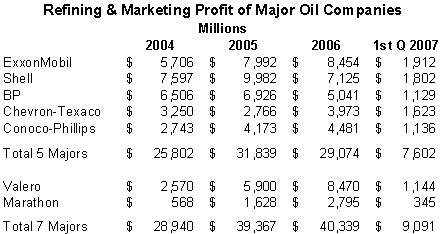

Now some will argue that a major portion of these profits has been realized by the upstream (exploration and production) stage of the industry due to high oil and gas prices which are out of the control of these companies. While we might debate the degree to which there is any control, Table 2 shows the trend in profits for the refining and marketing segments of these same five majors. Refining and marketing profits for them were $25.8 billion in 2004, and rose 23 percent in 2005 to $31.9 billion, and declined only slightly in 2006. When one includes two other major domestic refiners, Valero and Marathon, the totals increase to $39.4 billion in 2005 and $40.3 billion in 2006, up from $29 billion in 2004. Table 2

At the refinery level, refining margins have increased dramatically in recent years to record levels. According to Muse Stancil, & Co., the average refining margin for a Gulf Coast refiner in 2004 was a “healthy” $6.16 per barrel up from $2 per barrel in 2002. In 2005 that figure doubled to $12.53 and remained at about the same level in 2006 ($12.49 per barrel). West Coast refiners, which enjoy unusually low crude prices and unusually high product prices, enjoyed refining margins of $11.76 per barrel in 2004, $20.55 per barrel in 2005 and $23.73 per barrel in 2006. Finally, at times the industry has attempted to downplay the level of its profits by pointing to return on sales (operating profit divided by revenues) as the proper measure of profits for this industry. Such attempts to explain away the high level of profits are belied by the oil companies’ own statements which point to return on capital employed (RoCE) as the most appropriate measure of the industry’s profitability. As ExxonMobil states in its annual Financial and Operating Review:

The other majors all use RoCE as their preferred measure of profits; as Table 3 shows, they have generated a very healthy return. In contrast, the all-industry average is generally in the range of 9 to 12 percent. Table 3 Return on Capital Employed

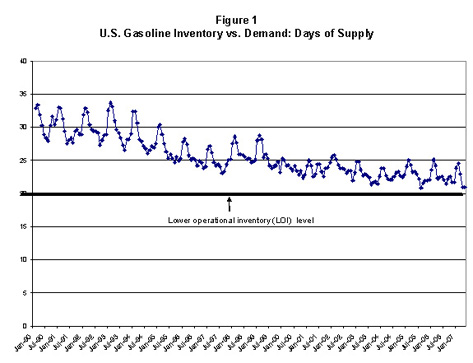

Explanation for Gasoline Price Increases The most frequent explanations offered for the rash of gasoline price increases in recent years have been refinery outages, pipeline or other transportation disruptions, unexpected increases in gasoline demand, refinery capacity constraints and increases in crude oil prices. Of these explanations, increases in crude oil costs should not result in an increase in profits. On the other hand, each of the other explanations reflects an imbalance between supply and demand which can lead to higher profits. Indeed, the industry rationalizes its price increases and the consequent profit increases on the basis of this imbalance, arguing that if prices did not increase by the amounts that they have, shortages would develop and gas lines would become the norm.[1] Higher prices are required to bring forth additional supply. The economic theory underlying this explanation of course assumes a reasonably competitive marketplace where the excess profits earned from the short-run price increase are reinvested so that supply is adequate to meet a future disruption. Unfortunately, this is where the paradigm breaks down. Decline in Inventories Throughout the 1990s and into this decade, the major oil companies have continually drawn down their working inventory levels for gasoline at the same time that demand for gasoline has risen. As a general matter, gasoline prices will track the underlying costs of production plus some element for profit. However, in the short run, gasoline prices rise and fall in response to movements in supply and demand. Inventories are an element of supply that can play an important role in these short-run supply movements and corresponding price fluctuations. Inventories serve several roles in this regard. First, inventory is used as an operational necessity – line fill in pipelines, tank bottoms, in-transit flow, etc. This form of inventory is typically not available to meet demand as it is required to keep the system running. Second, inventory is a component of supply that may be used to meet future demand, and thus provides a balancing element between supply (production) and demand. Third, inventories can be thought of as a “strategic” variable that can be used to economic advantage. Some companies term this “discretionary” inventory because it exceeds the level of normal operational needs, and is used to enhance the company’s profits. Inventories will normally exhibit patterns typical of seasonal demand and supply fluctuations, especially for a product such as gasoline that is subject to seasonal patterns. Inventories also should provide a buffer or protection against short-term supply disruptions. The National Petroleum Council (NPC) has defined a “target” operating inventory level or “lower operational inventory” (LOI) level which may be considered “the lower end of the demonstrated operating inventory range updated for known and definable changes in the petroleum delivery system.”[2] Elsewhere the NPC defines the LOI for motor gasoline for the United States to be approximately 185 million barrels. At today’s demand levels this is equal to about 20 days of gasoline supply.[3] “Days of supply” represent the number of days forward that inventory is available to cover demand. Various analysts have commented that 20 days of supply is the absolute minimum operational inventory the system can maintain, and once inventories fall below this level, the system has little or no flexibility and one may expect price spikes. Stated another way, normal operations are subject to serious disruption should stocks fall below this level. Most analysts see a causal link between gasoline inventories and wholesale and retail gasoline prices. Prior research has shown that as inventories reach low levels, prices do tend to rise and profit margins will also tend to increase. In each of the studies performed by EIA and the FTC of recent (since 2000) episodes of gasoline price spikes, they found that just prior to the onset of the price spike, inventory levels were “abnormally” or “critically” low. Finally, as inventory levels decline and prices rise, profit margins at the wholesale level increase significantly.

Total gasoline stocks in the United States have been declining since the early to mid-1990s. Figure 1 shows gasoline days of supply in the United States between 1990 and 2007. As can be seen there has been a gradual, yet continual decline in the volumes of gasoline inventory carried relative to demand. Whereas in 1990 the average days of supply level was about 30 days, that level fell to 23.8 days by 2000 and more recently to about 22.6 days of supply, precariously close to the bare minimum of 20.5 days of supply. The oil companies have made the conscious decision to reduce inventories throughout the country since the early 1990s even though demand has been steadily growing. The companies say the reduction is due to improved efficiencies in the system, utilization of “just-in-time” inventory methods, and use of sophisticated computer software that closely monitors demand and supply. Because inventory is considered working capital, the companies state that it is a cost of doing business, and they seek to minimize those costs, i.e., inventory levels, while attempting to maintain what they term “reliable supply systems.”

Yet the system itself is moving closer and closer to the breaking point such that any little “hiccup” in terms of a supply curtailment, even one that lasts only a couple of days, can cause precipitous price spikes. This was not the case prior to the year 2000 when the companies carried larger inventories. Refinery outages, pipeline and barge accidents are not unusual events. Throughout the history of this industry, companies have experienced refinery outages and other unanticipated supply disruptions. However, prior to 2000, the companies generally carried sufficient inventories to act as a buffer to prevent price spikes when such events occurred. Such disruptions now inevitably lead to price increases because inventories are not available or sufficient to offset these disruptions.

The industry says lower inventories save money and the savings are passed on to consumers. While this may be true, it ignores the cost to consumers of the price spikes that inevitably go along with these lower inventory levels. Since 2000, the country has averaged at least one price spike in most of the country each year. Even if each price spike is relatively short-lived, say two months, the increase in profits costs consumers more than any potential savings from lower inventory levels, assuming such savings are passed on. This may be shown in the following example based on the history of price spikes in recent years.

Our analysis of the price spikes since 2000 indicates that the average spike has lasted 3 months and cost consumers on average $0.15 per gallon. At a daily consumption level of 9 million barrels per day (or 378 million gallons per day), that is equivalent to a cost to consumers each year of $5.1 billion (378,000,000 * 90 days * .15 = $5,103,000,000). On the other hand the reduction in days of supply from the end of 1999 to the present has been approximately 3 days of supply or about 1.134 billion gallons. At a monthly storage cost of $0.02 per gallon, that is an annual savings of $22.6 million which means the net cost to consumers (assuming all of the cost savings is passed on) is $4.9 billion per year. This represents a pure wealth transfer from consumers in this country to the industry. Another way to think of this is that the industry has shifted the risk of short-term supply disruption away from itself and placed the risk and price impact squarely on consumers. Finally, the economic theory that the industry relies on to justify the price increases when supplies are not available, also states that in a competitive market certain companies will take advantage of future supply disruptions by carrying additional “strategic” inventories to meet the shortfall, gain market share and earn higher profits at the expense of those without supply. As we have seen in Figure 1, however, the industry has not opted for this “competitive” market strategy, but rather maintains low inventories to reap the collective benefits of when supply disruptions and price spikes do inevitably occur. Reinvestment of Industry Profits The other element of economic theory related to the justification for price increases in time of supply shortfall is that higher prices and their consequent higher profits will create an incentive for refiners to bring more supply into the market. This includes reinvestment of those profits into storage facilities (to maintain higher inventories) and in added refining capacity to produce more gasoline. Yet review of the data over the last two years of the majors’ investment in refining capacity suggests that very little money has been expended by the majors to increase refining capacity.

The majors have increased the amount they have invested in refining and marketing of late, but the vast majority of that investment has not gone toward increasing capacity (or gasoline manufacturing capacity). Indeed the top five majors have increased their investment in refining and marketing from $10.6 billion in 2004 to $12 billion in 2005 and $15 billion in 2006. However, the bulk of new refining investment has centered on meeting new EPA low sulfur gasoline and diesel standards and to improve refiners’ ability to handle heavy, high sulfur crude oil. Neither purpose increases capacity, but only helps the industry improve its profits. Shell in its 2006 annual reports states with regard to its downstream investment:

BP noted its sizeable investment in one refinery to handle heavy crude from Canada:

And Conoco-Phillips noted that it had too had invested in additional heavy crude processing capability:

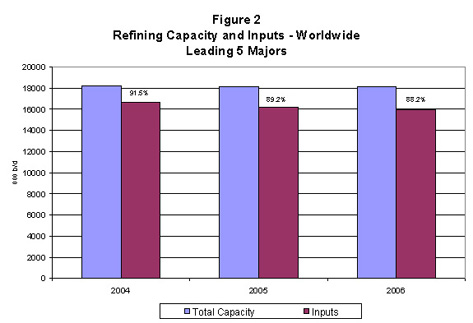

Figure 2 shows the changes in total refining capacity and inputs for each of the last three years for the five majors as a whole, both in the United States and throughout the world. As can be seen, total capacity and total input to that capacity has actually declined between 2004 and 2006. Inputs to capacity have declined more which means that capacity utilization has declined as shown by the percentages above the input bars in Figure 2.

Thus, the industry has not taken action to expand in any significant way its ability to produce more gasoline, and the majors as a group have actually decreased their total refining capacity. (In fact, Shell and BP have reduced their refining capacity while Conoco-Phillips increased its capacity and the other two have remained at about the same level.) Again, this runs counter to the economic theory that is used to justify gasoline price increases. Rather than reinvesting the high profits earned from these high prices in expanding the supply of gasoline, to the extent they have increased their investments in refining, the industry has largely directed that investment in ways to further increase their profits by making their refineries better suited to handle less expensive crude oils. However, perhaps more important is the fact that the increase in the amount invested pales in comparison to the huge profits that these companies are earning. For example, in 2006, the top 5 majors earned almost $120 billion in profits, yet spent only $15 billion on refining and marketing investments. In prior years when profits were not nearly as high, these companies were investing smaller amounts in refining and marketing, but they have not increased their investment on a proportionate basis.

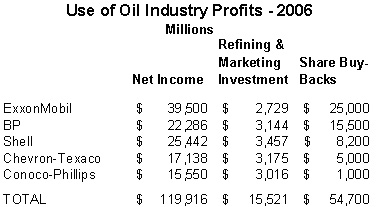

Where Have All the Profits Gone? The plain fact of the matter is that the bulk of the increased profits the industry has been earning has gone to relatively non-productive uses and certainly do not reflect what one would expect under the economic paradigm the industry is using to justify its price increases. The companies have been able to increase dividends to their shareholders, which obviously keeps them happy and willing to put up more capital. However, a major use of these “windfall” profits has been to buy back outstanding shares of stock. Table 4 summarizes this trend for 2006, comparing total profits earned with the amounts invested in refining and marketing investments and the amount used for share buy-backs. As can be seen, with most companies the amount used to buy back outstanding shares dwarfs the amount being reinvested in refining and marketing infrastructure which we have seen is not even going toward increasing gasoline supply. The buy-back of shares is not a productive use of these profits as it does not contribute to the growth of the company as reinvestment would. Furthermore, such action is inconsistent with the economic theory that the industry relies on to justify the price increases that create these profits to begin with. Industry, if it were behaving consistent with economic theory, would not be using 45 percent of its profits to buy back its stock. Economic theory would dictate that instead industry should be reinvesting these profits to expand refining and especially gasoline manufacturing capacity so the industry would be ready to meet supply disruptions and prevent price increases that now seem a way of life. Table 4

Policy Implications Industry’s reliance on economic theory explains only half of the story of gasoline price increases. The industry has failed in two key areas to use its profits where economic theory says it should: (1) to maintain higher inventories and (2) to invest in more refining capacity. This failure results from industry’s collective decision to behave in a manner that is not consistent with economic theory or at least what the theory of competitive markets would suggest. Nonetheless, there is no necessary evidence of collusion in these decisions; indeed there is no real need for collusion because the major players in the industry recognize their interdependence[4] and also know that consumers have few alternatives to paying higher prices for gasoline. There are no good alternatives to driving our cars and so even when the price of gasoline rises 20 percent, the demand for gasoline declines by only a relatively small amount.[5] The industry is well aware of this economic reality and thus can act opportunistically whenever a minor supply disruption occurs by raising prices precipitously, knowing that demand will not slacken much, and consumers will pay the higher price. Furthermore, as all companies carry relatively low inventories, the likely response to a refinery or other supply disruption will not be a redistribution of market share but rather higher prices as that is a more profitable outcome for all involved. Collusion is not required because each company recognizes that others cannot react by introducing more supply into the market. Consumers bear the cost of these price increases and industry shows no signs of reversing this trend. From a policy perspective, some action must be taken to increase investment in refining and gasoline manufacturing capacity as well as to stimulate an increase in the stocks of gasoline and other petroleum products. Some have suggested that the government move into the refining and marketing business. Others have suggested a tax on the windfall profits be used to stimulate investment. What is clear is that industry on its own has no real incentive to take action, other than to make relatively modest investments to keep the system operating on the edge so that supply disruptions will continue to create the opportunity for large price increases. Action must be taken, however, to ensure that the second half of the economic truth related to gasoline price increases comes to fruition, namely major reinvestment in additional refining capacity and increases in inventories. [1] Where demand exceeds supply, for example due to a refinery disruption, a competitive equilibrium will result with an increase in price and the quantity sold will decline. [2] This term was first coined by the NPC in its 1998 report, “U.S. Petroleum Product Supply – Inventory Dynamics,” and it is also used in its updated report, “Observations on Petroleum Product Supply: A Supplement to the NPC reports,” NPC, December 2004. The Energy Information Administration of the Department of Energy also uses this term and notes that the LOI is indicative of a situation where inventory-related supply flexibility could be constrained or non-existent. It is similar to the concept of “minimum operating inventory” (MOI) level. [3] Demand for gasoline is about 9.3 million barrels per day; inventories of 185 million barrels is equivalent to about 20 days of supply (185/9.3). [4] The downstream segment of the industry is what economists term an oligopoly which means an industry with few sellers who recognize that their behavior is interdependent where the actions of one firm will impact others. Other mechanisms such as the use of exchange agreements enhance this interdependence, all of which leads to less competitive behavior. [5] In economic theory this is what is known as the price elasticity of demand. Gasoline is considered price “inelastic” which means that large increases in price induce only small reduction in demand or consumption. Various analysts have estimated the price elasticity of demand for gasoline at approximately -.20 which means that a 20% increase in the price of gasoline will lead to only a 4% decline in demand. This is also consistent with recent surveys of drivers who have said that gasoline prices would have to eclipse $4 per gallon before they would alter their driving behavior.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||